In the bustling markets of the Middle East, one culinary staple stands out not just for its rich, nutty flavor but also for a curious physical behavior that has puzzled home cooks and chefs alike: the separation of oil and solids in tahini. This thick paste, made from ground sesame seeds, is a cornerstone of dishes like hummus and baba ganoush, yet it often arrives in jars with a layer of golden oil floating atop a dense, stubborn layer of sediment. This phenomenon, while entirely natural, can be off-putting to the uninitiated, leading to frantic stirring or even discarded jars. But understanding the science behind this separation not only demystifies the process but also empowers us to handle tahini with confidence and grace.

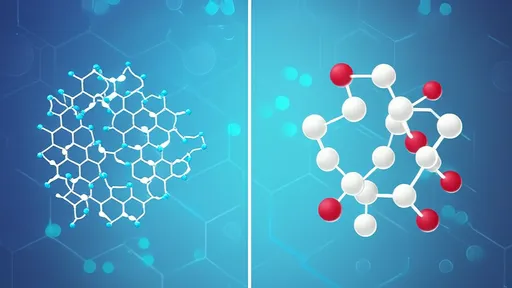

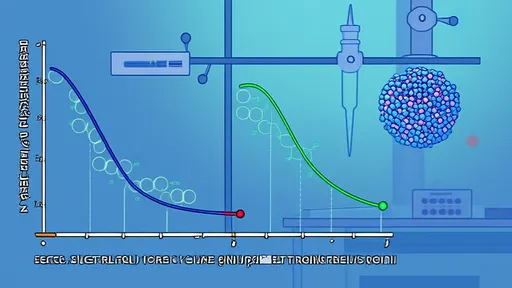

The physics of tahini separation is rooted in the basic principles of colloidal suspensions and density differences. At its core, tahini is a mixture of finely ground sesame particles suspended in their own natural oil. During grinding, the cellular structure of the sesame seeds is broken down, releasing oil that acts as a continuous liquid phase, while solid particles—comprising proteins, fibers, and other micronutrients—form a dispersed phase. Over time, gravity exerts its influence, causing the heavier solid particles to settle at the bottom of the container, while the lighter oil rises to the top. This process, known as sedimentation, is accelerated by factors such as temperature fluctuations, which affect the viscosity of the oil; warmer environments make the oil thinner, allowing particles to settle faster, while colder conditions can slow the separation but may also cause the oil to solidify, creating a different set of textural challenges.

Moreover, the stability of the emulsion plays a crucial role. Unlike manufactured emulsions like mayonnaise, which contain emulsifiers (e.g., lecithin in egg yolks) to bind oil and water phases, tahini lacks such stabilizers. Sesame seeds do contain natural emulsifiers, but they are often insufficient to maintain a homogeneous mixture indefinitely. As a result, the system inevitably moves toward equilibrium, with phases separating to minimize surface energy. This is why commercial tahini brands sometimes add stabilizers or recommend vigorous shaking—but in its pure form, separation is a sign of a minimally processed product, not a defect. Recognizing this can shift our perspective from frustration to appreciation, as it reflects the authentic, unadulterated nature of the ingredient.

When faced with a separated jar of tahini, the goal is to reintegrate the oil and solids without compromising its texture or flavor. The most effective technique is gradual, patient stirring. Start by opening the jar and using a long, sturdy utensil, such as a knife or chopstick, to gently loosen the solid layer from the bottom. This initial step is critical; forcing immediate vigorous stirring can lead to clumping or uneven mixing. Once loosened, begin stirring in a slow, circular motion, gradually incorporating the oil from the top into the solids. As the mixture becomes more fluid, you can increase the intensity of stirring, but avoid whisking or beating aggressively, as this might incorporate air and alter the dense, creamy consistency that is ideal for recipes like halva or sauces.

For particularly stubborn separation, especially in cold climates where the oil may have solidified, mild warming can be beneficial. Place the sealed jar in a bowl of warm water for 10–15 minutes, ensuring the water does not enter the container. This gently lowers the oil's viscosity, making it easier to blend. However, avoid using high heat or microwaving, as excessive heat can degrade the flavor and nutritional quality of the tahini. After warming, proceed with the stirring method described above. Once homogenized, storing the tahini at a consistent room temperature—away from direct sunlight or heat sources—can slow future separation. Some enthusiasts even recommend storing the jar upside down for short periods to encourage natural reintegration, though this is more anecdotal than scientifically proven.

Beyond immediate fixes, understanding tahini's behavior can inform how we use it in cooking. For instance, if a recipe calls for tahini as a binding agent—such as in dressings or dips—it's wise to fully integrate the jar first to ensure consistent measurement and texture. Conversely, in some traditional recipes, a layer of oil on top is actually desired for sealing and preserving the paste, so always check cultural context. Additionally, if you frequently use tahini, consider transferring it to a narrow, tall container rather than a wide jar; this reduces the surface area and can slow sedimentation. Ultimately, embracing the separation as part of tahini's character allows us to work with it rather than against it, turning a potential kitchen nuisance into an opportunity for deeper engagement with our ingredients.

In conclusion, the oil-and-solids division in Middle Eastern tahini is a fascinating example of everyday physics in action, driven by gravity, density, and the absence of emulsifiers. Rather than a flaw, it is a testament to the product's purity and natural origins. With simple techniques like gradual stirring and cautious warming, we can easily restore its smooth uniformity, while proper storage can manage future separation. By appreciating the science behind this behavior, we not only become more adept in the kitchen but also connect more intimately with the cultural heritage of this beloved ingredient. So next time you open a jar of tahini and see that layer of oil, remember: it's not a problem to solve, but a phenomenon to understand and master.

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025