In the intricate world of protein science, the thermal denaturation behavior of proteins serves as a critical window into their structural stability and functional properties. Among the myriad of proteins studied, ovalbumin and myosin stand out due to their distinct roles in biological systems and industrial applications, particularly in the food industry. The coagulation differences between these two proteins, as revealed by their thermal denaturation curves, not only underscore fundamental biochemical principles but also have profound implications for texture and quality in protein-based products.

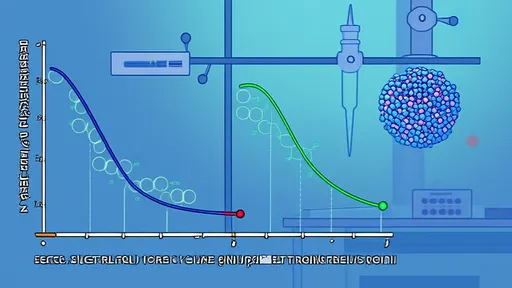

Ovalbumin, the predominant protein in egg white, is a globular protein known for its relatively stable structure under native conditions. When subjected to increasing temperatures, ovalbumin undergoes a cooperative unfolding process. The thermal denaturation curve typically exhibits a sharp transition, indicative of a highly cooperative denaturation event. This transition, often occurring around 84°C for ovalbumin in its native state, reflects the simultaneous unfolding of its domains. The steep slope of the curve suggests a narrow temperature range over which the protein transitions from a folded to an unfolded state. Following denaturation, ovalbumin molecules aggregate and form a fine, gel-like network. This coagulation results in a soft, elastic gel, which is a desirable texture in many culinary applications, such as in the setting of custards or the structure of baked goods. The denaturation process is largely driven by the disruption of hydrogen bonds and the exposure of hydrophobic regions, which subsequently interact to form the gel matrix.

In stark contrast, myosin, the primary protein component of the thick filaments in muscle fibers, presents a more complex denaturation profile. Myosin is a fibrous protein with a long, helical tail and a globular head, and its thermal behavior is less cooperative than that of ovalbumin. The thermal denaturation curve for myosin is often broader and may display multiple transitions, corresponding to the unfolding of different domains within the protein complex. The myosin head (S1 subfragment) denatures at a lower temperature, typically around 55-60°C, while the rod portion (light meromyosin) is more thermally stable, denaturing at higher temperatures, around 60-70°C or even higher depending on the specific conditions and source. This multi-step denaturation means that myosin does not coagulate in a single, sharp event. Instead, its coagulation is a gradual process. As the heads denature first, they initiate aggregation, but the persistent stability of the rod regions allows for the formation of a different kind of gel network. Myosin gels are known for their strength and rubbery texture, which is crucial for the firmness of cooked meat products. The aggregation involves extensive cross-linking, often facilitated by disulfide bonds and hydrophobic interactions, leading to a coarse, fibrous network rather than the fine matrix seen with ovalbumin.

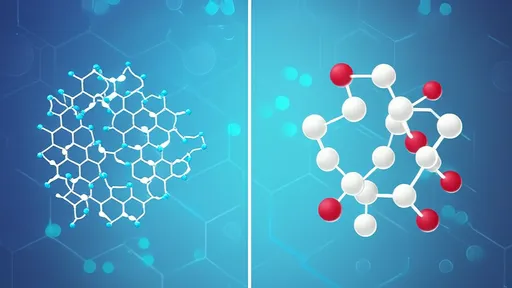

The fundamental differences in the coagulation behavior between these two proteins can be traced back to their native structures and amino acid compositions. Ovalbumin's structure is compact and globular, stabilized by disulfide bonds and a significant number of intramolecular hydrogen bonds. Its denaturation is a classic example of a two-state transition from the native to the denatured state. The exposed hydrophobic patches after unfolding readily interact with those on other molecules, leading to a relatively homogeneous aggregation process. Myosin, however, is an elongated dimer with distinct functional domains. Its complexity means that denaturation is not an all-or-none process. The independent unfolding of its subdomains creates opportunities for different types of intermolecular interactions at different stages of heating. This results in a more heterogeneous aggregation and a consequently different gel morphology.

Environmental factors such as pH, ionic strength, and the presence of other solutes further modulate these denaturation curves and the resulting coagulation. For instance, a shift in pH away from ovalbumin's isoelectric point (pI ~4.5) can alter the net charge on the protein, either stabilizing it against thermal denaturation or promoting aggregation at lower temperatures by reducing electrostatic repulsion. For myosin, salt concentration is a critical factor. High ionic strength can screen charges and promote the assembly of myosin into thick filaments, which then denature and gel in a manner that significantly influences the texture of products like sausages or surimi.

Understanding the nuances of these thermal denaturation curves is not merely an academic exercise; it is a cornerstone of food science and technology. The ability to predict and control the textural outcome of heated protein systems is paramount. In the egg industry, processes are designed to gently pasteurize egg white without causing excessive denaturation that would lead to premature gelling. Conversely, in meat processing, thermal treatments are optimized to ensure myosin denaturation and gelation proceed in a way that yields the desired bite, moisture retention, and sliceability in products like ham or frankfurters. The difference between a tender scrambled egg and a tough, rubbery one, or between a juicy sausage and a dry, crumbly one, often boils down to the precise management of these protein denaturation and coagulation dynamics.

In conclusion, the thermal denaturation curves of ovalbumin and myosin tell a story of structural disparity leading to functional divergence. Ovalbumin, with its sharp, cooperative transition, begets a fine, elastic gel upon coagulation. Myosin, with its broad, multi-stage denaturation, forms a strong, fibrous gel. This dichotomy, rooted in the proteins' innate architectures, is a powerful reminder of how nature's molecular designs dictate macroscopic properties. For scientists and engineers, leveraging this knowledge allows for the sophisticated manipulation of texture in food products, turning the abstract concepts of protein unfolding into tangible quality on the plate.

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025