In the intricate world of microbial ecosystems, few interactions are as compelling as the symbiotic yet competitive dance between lactic acid bacteria and yeast. This dynamic, often observed in fermented foods and beverages, represents a fascinating case study in microbial ecology, where cooperation and rivalry unfold simultaneously within shared environments. The relationship is not merely a biological curiosity; it underpins processes central to food production, biotechnology, and even broader ecological principles.

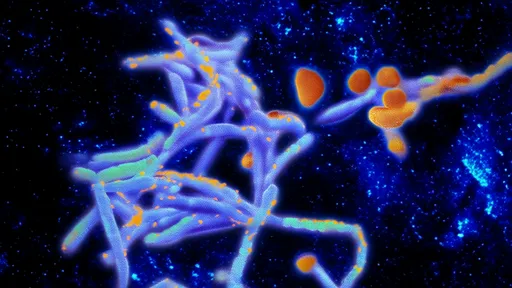

Lactic acid bacteria, a group comprising genera like Lactobacillus and Streptococcus, are renowned for their ability to convert sugars into lactic acid through fermentation. This metabolic pathway not only provides them with energy but also acidifies their surroundings, creating an environment hostile to many competing microorganisms. Yeasts, particularly Saccharomyces species, thrive on similar sugar-rich substrates but employ alcoholic fermentation, producing ethanol and carbon dioxide as primary metabolites. When these two microbial groups coexist, their metabolic activities create a complex web of interactions shaped by nutrient availability, environmental conditions, and evolutionary adaptations.

The foundation of their relationship often begins with a degree of mutualism. Yeasts, especially in the early stages of fermentation, can break down complex carbohydrates or produce vitamins and amino acids that lactic acid bacteria may struggle to synthesize independently. This nutritional support can enhance bacterial growth and acid production. In return, the acidic environment generated by lactic acid bacteria can inhibit the growth of molds and other pathogens that might otherwise outcompete or harm yeast populations. This cooperative aspect is elegantly demonstrated in traditional fermentations like sourdough or kefir, where stable consortia of yeast and bacteria have evolved to support one another’s survival.

However, this harmony is perpetually balanced on a knife’s edge of competition. Both microbes rely on the same limited resources—primarily sugars—and their metabolic end products can become antagonistic. As lactic acid bacteria lower the pH, the increasing acidity may eventually stress even acid-tolerant yeasts, potentially inhibiting their growth or ethanol production. Conversely, high concentrations of ethanol produced by yeast can be toxic to many bacterial species, including some lactic acid bacteria. This creates a feedback loop where each group’s success inadvertently threatens the other, leading to a natural oscillation in dominance depending on environmental conditions and initial inoculum levels.

Environmental factors such as temperature, oxygen availability, and nutrient composition further modulate this interplay. In anaerobic conditions, yeast may predominantly produce ethanol, intensifying its inhibitory effects on bacteria. Under slight oxygenation, yeast metabolism might shift, reducing ethanol output and altering the competitive landscape. Temperature optima also differ; some lactic acid bacteria thrive at slightly higher temperatures than certain yeasts, meaning small changes can tilt the balance of power. These variables ensure that no two fermentations are identical, with outcomes varying based on subtle contextual differences.

Evolutionary adaptations refine this delicate balance over time. Some yeast strains have developed tolerance to low pH and lactic acid, allowing them to persist in acidic environments. Certain lactic acid bacteria, in turn, exhibit resistance to ethanol or can utilize metabolites produced by yeast as energy sources. In stable, long-term associations—such as those in natural fermentation starters—these adaptations can lead to coevolution, where each party evolves traits that minimize conflict and maximize mutual benefit. This evolutionary arms race, however, is ongoing, with neutrality rarely being a sustainable outcome.

The implications of this microbial game extend far beyond academic interest. In the food and beverage industry, understanding and manipulating the lactic acid bacteria-yeast dynamic is crucial for product consistency, flavor development, and shelf stability. In sourdough bread, for instance, the ratio of bacteria to yeast influences acidity, rise, and taste. In winemaking, spontaneous fermentations driven by native yeast and bacteria can produce unique terroir-driven flavors, while controlled inoculations allow producers to steer outcomes predictably. Similarly, in dairy fermentations like yogurt or cheese, managing this relationship helps prevent spoilage and enhance texture.

Biotechnological applications are also emerging. Researchers are exploring co-cultures of yeast and lactic acid bacteria for sustainable production of biofuels, organic acids, and even pharmaceuticals. By harnessing their synergistic potentials—such as yeast breaking down lignocellulosic materials for bacteria to ferment—scientists aim to create efficient, low-waste bioprocesses. Conversely, understanding their competitive behaviors aids in designing interventions against undesirable microbial mixtures in industrial settings or even in medical contexts, where similar interactions occur in microbiomes.

Yet, many questions remain unanswered. How do quorum-sensing molecules or other forms of microbial communication influence this relationship? What role do bacteriophages or mycoviruses play in tipping the scales? How might climate change—altering temperature and sugar profiles in raw materials—affect these delicate balances in natural fermentations? Ongoing research employing genomics, metabolomics, and advanced computational models continues to unravel these complexities, promising deeper insights and novel applications.

In essence, the interaction between lactic acid bacteria and yeast epitomizes the broader principles of ecology: coexistence driven by a blend of cooperation and competition, shaped by environment, and refined by evolution. This microscopic game, though often overlooked, is a testament to the sophistication of microbial life and its profound impact on human culture, industry, and science. As we delve deeper into their world, we not only learn to better harness their capabilities but also gain a humbling perspective on the interconnectedness of life at all scales.

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025