In the misty coastal regions of Japan, where the Pacific Ocean meets rugged shorelines, a culinary tradition has been perfected over centuries that represents the very essence of Japanese umami. This is the world of katsuobushi, and specifically, the artisanal craft of creating and preparing the highest grade known as honkarebushi or Japanese dried bonito. The process is not merely a means of preservation but a transformative journey that turns the humble skipjack tuna into one of the most potent flavor foundations in global gastronomy.

The journey begins with the selection of the finest skipjack tuna, often caught in the rich waters around Japan. The fish are carefully beheaded, gutted, and filleted into specific sections that will eventually become the fushi, or the hardened blocks of dried fish. These sections are then arranged in baskets and simmered in carefully controlled temperatures, a process that cooks the meat while beginning the crucial concentration of flavors. The simmering time and temperature vary between master craftsmen, each guarding their specific approaches as family secrets passed down through generations.

Following the cooking process, the fish blocks undergo meticulous deboning by hand. Using specialized tools, craftsmen remove every small bone with precision, ensuring the structural integrity of the block remains intact. This stage requires years of experience to master, as any damage to the block can affect the entire drying process. The deboned blocks then enter the smoking phase, where they are smoked for weeks to months over specific hardwoods like oak or cherry. This smoking not only further dehydrates the fish but imparts subtle woody notes that complement the inherent umami characteristics.

The most critical phase comes next: fermentation and maturation. The smoked blocks are inoculated with Aspergillus glaucus mold, which grows on the surface and draws out remaining moisture while breaking down fats and proteins into amino acids. This process is repeated multiple times—the blocks are sun-dried during the day and allowed to mold at night—sometimes over several months. Each cycle intensifies the flavor and hardens the block further, eventually creating a piece so hard it resembles dark wood more than fish. The final product, honkarebushi, can have moisture content as low as 15%, making it one of the hardest food substances in the world.

The true magic of honkarebushi reveals itself in the final preparation. To access its deep reserves of flavor, one must use a specialized tool called a katsuobushi kezuriki, a plane specifically designed for shaving the rock-hard block. This traditional device, often made of beautiful woods with a sharp blade mounted at a precise angle, requires skill and practice to operate effectively. The craftsman places the block in the box-like holder and pushes it across the blade with steady, even pressure, creating delicate pink-brown shavings that curl like wood shavings but carry an incredible aroma of the sea, smoke, and profound umami.

The shaving technique itself is an art form that significantly impacts the final culinary application. Different dishes require different shave sizes and thicknesses. For dashi, the foundational broth of Japanese cuisine, larger, thicker shavings are preferred as they release their flavors more slowly during steeping, creating a clearer, more refined broth. Thinner, finer shavings are used as toppings for dishes like takoyaki or okonomiyaki, where they dance and sway from the heat, adding visual drama alongside their burst of flavor. The very act of shaving increases the surface area exponentially, allowing for maximum extraction of the fifth taste.

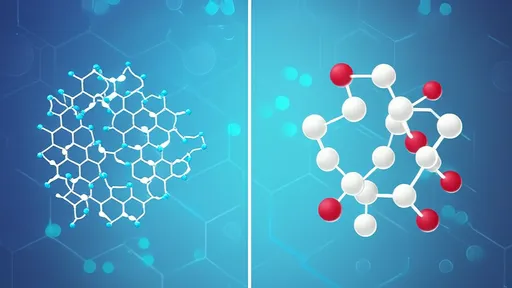

Scientifically, the importance of proper shaving technique relates directly to the release of flavor compounds. Honkarebushi contains exceptionally high levels of inosinate, a nucleotide that is the primary source of its umami character. Research has shown that the size and thickness of the shavings directly affect the rate and efficiency of inosinate extraction when steeped in water. Larger surface area relative to mass—achieved through thinner shavings—allows for quicker dissolution of these compounds. However, thinner shavings can also over-extract bitter compounds if left too long, hence the traditional practice of briefly steeping then immediately straining the dashi.

The timing between shaving and usage is equally critical. The shavings begin to oxidize immediately upon exposure to air, gradually losing their aromatic complexity and umami potency. This is why traditional Japanese kitchens always shave katsuobushi immediately before use, preserving the volatile compounds that give fresh katsuobushi its distinctive aroma. The difference between freshly shaved and pre-packaged katsuobushi is dramatic—comparable to the difference between freshly ground and pre-ground coffee beans.

Modern science has helped quantify what traditional craftsmen understood intuitively. Studies using liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry have identified over 200 volatile compounds in katsuobushi shavings, with concentrations changing dramatically based on shaving thickness and storage conditions. The ideal shaving thickness for dashi—approximately 0.03 to 0.05 millimeters—creates the perfect balance between surface area and structural integrity, allowing optimal extraction during the brief 2-3 minute steeping period that defines proper dashi preparation.

Beyond technical considerations, the art of katsuobushi preparation represents a philosophical approach to food that characterizes much of Japanese culinary tradition. It embodies the concepts of transformation through patience (the months-long drying process), respect for ingredients (utilizing every aspect of the fish), and precision in execution (the exacting shaving technique). Each step in the process, from fish selection to the final shaving, is performed with mindfulness and intention, resulting in a product that is far more than the sum of its parts.

Today, as global cuisine continues to embrace umami as a fundamental taste, the understanding and appreciation of katsuobushi has spread beyond Japan's borders. Michelin-starred chefs worldwide now keep katsuobushi kezuriki in their kitchens, shaving the hard blocks to order for incorporating this profound flavor into innovative dishes. Yet despite this international recognition, the heart of katsuobushi culture remains in the small coastal workshops of Japan, where master craftsmen continue centuries-old traditions, knowing that their painstaking work provides the foundation for one of the world's most refined culinary traditions.

The story of Japanese dried bonito is ultimately one of transformation—of simple fish into complex flavor, of traditional craft meeting modern science, and of local tradition finding global relevance. It stands as a testament to how human ingenuity, patience, and respect for nature can create something extraordinary from the most basic ingredients. As we continue to explore the depths of flavor, the lessons from katsuobushi—from its creation to its preparation—remain more relevant than ever in our pursuit of culinary excellence.

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025