The Maillard reaction, often described as the non-enzymatic browning process, represents one of the most complex and consequential chemical interactions in food science, pharmacology, and even cosmetic industries. While commonly associated with the appealing aroma of baked bread or seared steak, its underlying mechanisms involve a sophisticated dance between amino acids and reducing sugars under specific thermal conditions. The control theory of the Maillard reaction posits that by manipulating the protein-sugar ratio alongside precise temperature and time functions, we can predict, direct, and optimize the reaction's pathway and outcomes. This principle moves beyond culinary art into a realm of science where reproducibility and specificity are paramount.

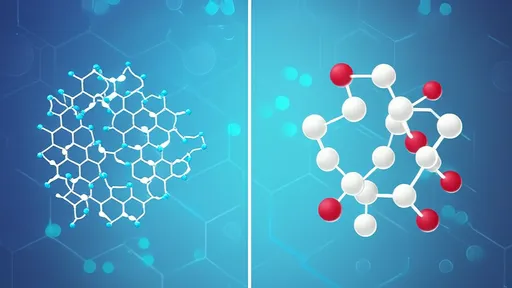

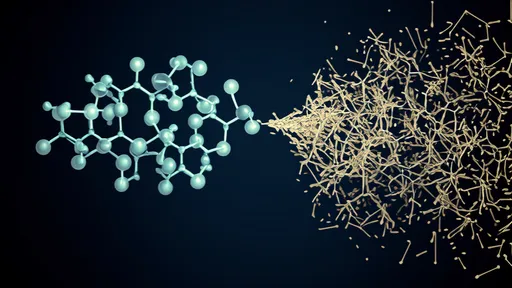

At its core, the Maillard reaction begins with the condensation of a carbonyl group from a reducing sugar and an amino group from an amino acid or protein, forming an unstable Schiff base. This intermediate quickly rearranges into a more stable Amadori compound, which then degrades through various pathways—depending on environmental conditions—into a multitude of flavor compounds, melanoidins for color, and sometimes undesirable by-products like acrylamide. The control theory emphasizes that the ratio of protein to sugar is not merely a matter of proportion but a determinant of which reaction pathways dominate. For instance, an excess of sugar in the system might drive the reaction toward furfural and hydroxymethylfurfural formation, while a higher amino acid concentration could favor Strecker degradation, producing aldehydes and pyrazines that contribute to nutty and roasted notes.

Temperature serves as the primary accelerator and director of the Maillard reaction. The relationship between temperature and reaction rate is exponential, governed by the Arrhenius equation, but control theory delves deeper into how temperature gradients influence specific product formation. Low-temperature, prolonged heating (e.g., 50-60°C for hours) tends to promote the formation of initial intermediates and certain flavor precursors without extensive browning, ideal for processes like milk pasteurization or the development of subtle flavors in fermented products. In contrast, high-temperature, short-duration exposures (e.g., above 150°C for minutes or seconds) drive the reaction rapidly toward melanoidins and crispy textures, characteristic of grilling or baking. However, exceeding threshold temperatures without control can lead to carbonization and the generation of carcinogenic compounds, underscoring the need for precise thermal management.

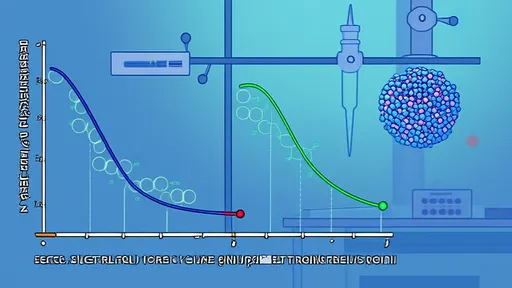

Time functions as the silent partner to temperature, modulating the extent of the reaction. In control theory, time is not linear in its effect; it interacts dynamically with temperature and concentration variables. Isothermal conditions might show a logarithmic progression in browning intensity, but in real-world scenarios where temperature fluctuates, time integrals become critical. For example, in industrial baking, the product’s thermal history—through different zones of an oven—must be modeled to ensure consistent color and flavor development. Retort processing in canned foods uses time-temperature combinations to achieve sterilization while minimizing undesirable Maillard outcomes like off-flavors or nutrient loss. The interplay between time and temperature can be visualized through kinetic models that plot reaction progress against energy input, often revealing optimal windows for desired outcomes.

The protein-sugar ratio intertwines with thermal parameters to define the reaction's destiny. Empirical studies have shown that a 1:1 molar ratio of amino groups to carbonyl groups often maximizes browning intensity, but this varies widely based on the specific reactants. Lysine-rich proteins, for example, react more readily with glucose than would proline, and disaccharides like sucrose require hydrolysis before participating, effectively altering the functional ratio. Control strategies must account for these nuances. In dairy processing, adjusting the lactose-to-casein ratio before thermal treatment can control the development of cooked flavors or desirable caramel notes. In plant-based meat alternatives, precise ratios of pea protein and reducing sugars are engineered to mimic the Maillard-derived flavors and colors of animal meat when heated.

Advanced applications of Maillard reaction control theory extend beyond food. In pharmaceuticals, Maillard reactions can lead to drug degradation, so formulations are designed with excipients that minimize reactive sugar concentrations or employ storage conditions that suppress the reaction. Conversely, in cosmetic chemistry, controlled Maillard reactions are harnessed to create natural colorants and sunscreen agents from amino acids and sugars. Each application demands a unique function of ratio, temperature, and time, often modeled through response surface methodology or computational predictive tools. These models transform the art of control into a science, enabling the design of processes that yield precise sensory or chemical attributes.

Despite the progress, challenges remain in fully mastering the Maillard reaction. Its network of parallel and sequential reactions means that changing one variable can have unforeseen effects downstream. Multivariate control systems, often aided by real-time monitoring like spectroscopy, are becoming essential for industrial precision. Moreover, health concerns around advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) necessitate control strategies that balance desirable qualities with nutritional safety. Future directions may involve the use of enzymes to steer the reaction or the development of novel inhibitors that block harmful pathways without affecting flavor or color.

In essence, the control theory of the Maillard reaction—centered on the deliberate manipulation of protein-sugar ratios, temperature, and time—represents a convergence of chemistry, engineering, and sensory science. It moves from passive observation to active design, allowing us to harness one of nature’s most versatile reactions for innovation across industries. As research unravels more of its complexities, the ability to precisely direct this reaction will continue to grow, offering new possibilities for creating healthier, more sustainable, and more appealing products.

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025