In the world of culinary chemistry, few transformations are as universally recognized yet chemically intricate as the conversion of sucrose into caramel. This process, known as caramelization, is not merely a change in color or flavor but a profound molecular journey involving the breakdown and reorganization of chemical bonds. It is a dance of atoms and energy that turns the familiar sweetness of table sugar into the complex, rich notes that define caramel.

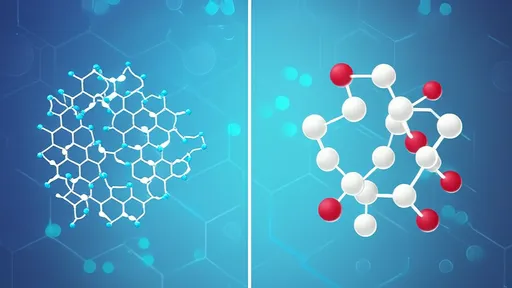

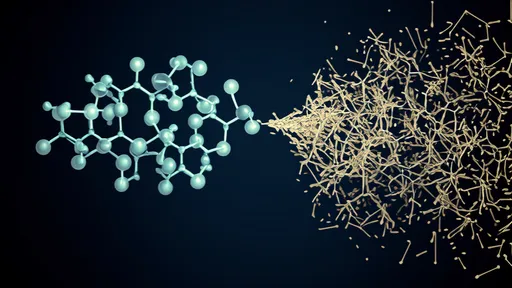

At its core, sucrose is a disaccharide composed of two simpler sugars: glucose and fructose. These units are linked by a glycosidic bond, which acts as a bridge holding the molecule together. Under normal conditions, this structure is stable, providing the crystalline solid we commonly use. However, when heat is applied, typically around 160 to 180 degrees Celsius, the energy input becomes sufficient to initiate the cleavage of this bond. This rupture is the first critical step in caramelization, effectively liberating glucose and fructose monomers from their combined form.

Once freed, these monosaccharides enter a phase of dynamic instability. The heat continues to drive dehydration reactions, where water molecules are ejected from the sugar structures. This loss of water triggers a cascade of reactions, including enolization and isomerization, leading to the formation of various intermediates such as difructose anhydride or other sugar isomers. These compounds are transient, often existing only momentarily before proceeding to subsequent changes.

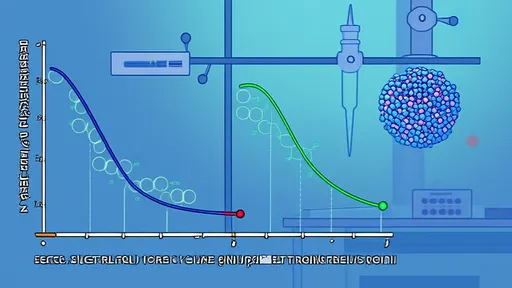

As the temperature sustains or increases, fragmentation reactions take center stage. Here, the sugar molecules break down into smaller, volatile compounds like diacetyl, acetol, or furans. These fragments are responsible for the early aromatic profiles developing during caramelization—notes that might be buttery, nutty, or slightly acidic. Concurrently, polymerization begins, where smaller molecules link together to form larger, complex polymers. This stage is marked by the emergence of melanoidins and other macromolecules, which contribute significantly to the color and viscosity of caramel.

The recombination of these fragments and polymers is where caramel truly finds its identity. Through aldol condensation and other coupling reactions, new carbon-carbon bonds form, creating compounds with extended conjugated systems. These systems absorb light in the visible spectrum, yielding the characteristic amber to deep brown hues. The flavor profile deepens simultaneously, incorporating hundreds of distinct compounds that offer notes of toffee, bitterness, and warmth. Factors such as temperature, time, pH, and even the presence of catalysts like acids or salts can steer these reactions, resulting in caramels of varying color intensity and taste complexity.

Industrially, caramelization is harnessed with precision. In food production, type of caramel—whether for coloring, flavoring, or both—is controlled by manipulating reaction conditions. For instance, a higher temperature might be used to produce a dark caramel for cola beverages, while a slower, controlled heat application could yield a lighter caramel for confectionery. The chemistry behind this is leveraged to achieve consistency and desired functional properties, such as solubility or stability in various products.

Despite its widespread application, caramelization is distinct from the Maillard reaction, though they are often concurrent in cooking. The Maillard reaction involves amino acids and reducing sugars, while caramelization is purely sugar-based. This difference is crucial for understanding flavor development in different culinary contexts. Pure caramelization offers a spectrum of flavors that are inherently sweet and carbon-rich, without the nitrogenous compounds that create meaty or roasted notes in Maillard products.

From a nutritional standpoint, caramelization alters the composition of sugars. The process reduces the overall sugar content through decomposition and polymerization, and it generates compounds like caramelan or caramelen, which are less sweet but contribute to texture and color. However, it can also produce acrylamide in trace amounts if certain conditions are met, though this is more typical in Maillard reactions. Thus, while caramel adds depth and appeal, its consumption is often considered in the broader context of dietary intake.

In scientific research, the study of caramelization extends beyond the kitchen. It serves as a model system for understanding pyrolysis and thermal degradation of carbohydrates. Insights gained here apply to fields as diverse as food science, organic chemistry, and even biofuel production, where sugar breakdown is a key step. The precise mechanisms continue to be unraveled using advanced analytical techniques like mass spectrometry and NMR, revealing ever-greater details about the isomerization and bond reorganization events.

Ultimately, the journey from sucrose to caramel is a testament to the transformative power of heat and chemistry. It is a process where simple sugars, through the breaking and making of bonds, evolve into a multitude of compounds that delight the senses. Whether in a simple caramel sauce or a complex industrial flavoring, this reaction showcases how fundamental chemical principles manifest in everyday experiences, blending science with art in every sticky, golden drop.

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025