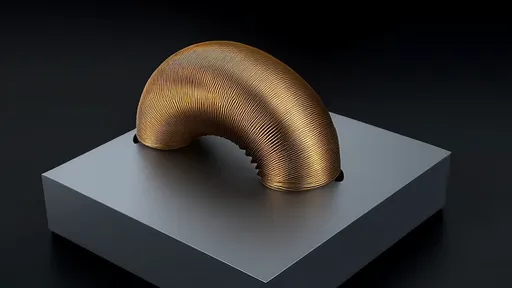

In the vast, silent theater of interstellar space, two emissaries from Earth continue their silent, steadfast journey. The Voyager 1 and 2 spacecraft, launched in 1977, carry with them perhaps the most profound and poetic message ever sent: the Golden Records. These gilded phonograph records are time capsules, intended to communicate the story of our world to any extraterrestrial intelligence that might one day find them. But beyond the curated sounds of greetings, music, and nature, lies a deeper, more technical narrative—one written not in melodies or words, but in the very fabric of the recordings themselves. This is the story told through spectral analysis, the study of the Golden Record's sonic fingerprints.

The concept of the Golden Record was spearheaded by a committee led by the visionary astronomer Carl Sagan. The task was monumental: to select a representative sample of Earth's cultural and natural sounds that could convey the essence of humanity and our planet. The result is a 90-minute audio montage, a rich tapestry that includes spoken greetings in 55 languages, a selection of music from across the globe and across centuries, the sounds of nature, and even the brainwaves of a young woman in love. Yet, for all its curated content, the record's most authentic signature may be an unintended one, embedded in the technical characteristics of its mid-20th-century recording technology.

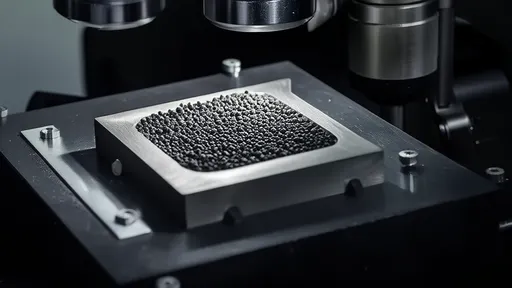

Spectral analysis, in its essence, is the process of decomposing a complex sound wave into its constituent frequencies, much like a prism separates white light into a spectrum of colors. This analysis reveals not just what was recorded, but how it was recorded. It maps the amplitude of each frequency present, creating a unique acoustic signature often referred to as a sound's "voiceprint" or spectrogram. When applied to the Golden Record, this technique transforms from a mere technical exercise into a form of archaeological audio forensics. It allows us to listen not only to the content but to the medium itself, to hear the subtle whispers of the recording equipment, the studio environments, and the mastering process that together gave the record its final form.

The sonic palette of the Golden Record is breathtakingly diverse. The spectral analysis reveals this diversity with stunning clarity. The low, resonant frequencies of a crashing wave or the rumble of a volcano paint broad, powerful strokes on the lower end of the spectrogram. The intricate, high-frequency harmonics of a Bach Brandenburg Concerto or the sharp, percussive attack of a Senegalese percussion piece create delicate, complex patterns higher up. The human voice, from the guttural clicks of a !Kung greeting to the melodic tones of Mandarin, occupies its own distinct territory. Each track, each sound, leaves a unique spectral fingerprint, a visual representation of its acoustic soul. This analysis does not diminish the art; it adds a new dimension to it, providing a graphical score for the symphony of Earth.

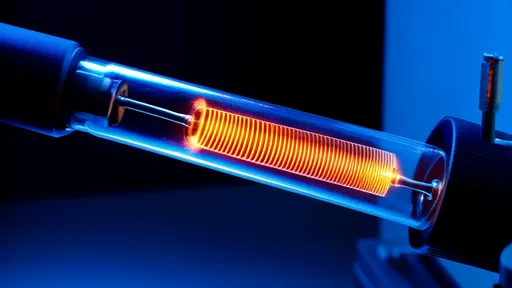

However, the most compelling story the spectrogram tells is not of the sounds themselves, but of the technological context of their creation. The late 1970s was a specific moment in audio engineering, a transition period between analog warmth and the dawn of the digital age. The recordings on the Golden Record were sourced from various analog formats—vinyl LPs, magnetic tape reels, and direct-to-disc cuts. A keen spectral analysis detects the tell-tale signs of this era. There is a palpable warmth, a slight compression of the dynamic range characteristic of analog mastering. One might detect the gentle, inaudible-to-humans hum of tube amplifiers or the very specific frequency response of the Neumann U47 microphones likely used in some sessions. There is a tangible noise floor—a soft, consistent hiss underlying the silence—that is the acoustic equivalent of grain in a photograph. This is not noise to be filtered out; it is historical data. It is the sound of 1977.

This embedded technological signature transforms the Golden Records into something even more profound than a message. They become artifacts. A future civilization, or even our own descendants recovering the probe in a distant millennium, could use this spectral data. By analyzing the frequency anomalies, the distortion patterns, and the noise profiles, they could potentially reverse-engineer the recording technology itself. They could deduce the materials used in the stylus that cut the master disc, the composition of the vinyl, and the rotational speed of the turntable. The record becomes its own Rosetta Stone, providing the technical key to its own playback and understanding. It doesn't just say "hello"; it explains the language and the mouth that spoke it.

Contemplating the Voyager probes' journey adds a layer of almost unimaginable poignancy to this analysis. They are now in interstellar space, beyond the protective heliosphere of our Sun, traveling through a near-perfect vacuum. The records, sealed in their aluminum jackets, are subjected to the relentless, if incredibly sparse, bombardment of cosmic rays and interstellar dust. Over millions of years, these forces will cause infinitesimally slow degradation. A spectral analysis performed a million years from now would likely reveal a different voiceprint—one etched with the scars of an epic journey. The high frequencies, the most fragile, may be the first to attenuate, slightly muffling the brilliance of the violins and the songbirds. The pristine silence between sounds would be filled with the faintest crackle of atomic-scale damage. The record's story would then be twofold: the story of Earth circa 1977, and the story of its long, silent voyage through the galaxy.

The Golden Record is often celebrated for its content—the music of Beethoven, the greetings of children, the sound of a kiss. But its true genius lies in its totality. It is a snapshot, frozen in gold, of a moment in technological and cultural history. The spectral analysis of its sound reveals the hidden layers of this snapshot. It allows us to see the brushstrokes, the type of canvas, and the varnish used by its creators. It is a testament to the idea that every message is inevitably bound to the medium that carries it. The Voyagers' Golden Records are not just messages from Earth; they are pieces of Earth, carrying our sounds, our science, and our signature into the cosmic dark, whispering our story in a language of frequencies and waves for as long as their golden surfaces endure.

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025