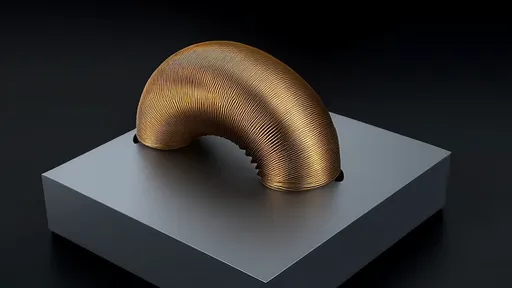

In the intricate world of mechanical horology, few components are as fundamental yet as elegantly complex as the balance spring, or hairspring, of a clock. This fine, spiral-coiled spring lies at the very heart of a mechanical timekeeper's soul, governing its rhythm and accuracy. The relationship between its elastic deformation and the resulting vibration frequency is not merely a topic of academic interest; it is the cornerstone upon which the entire science of mechanical time measurement is built. For centuries, watchmakers and engineers have manipulated this relationship, striving for the elusive goal of perfect isochronism—where the period of oscillation remains constant regardless of the amplitude of the swing.

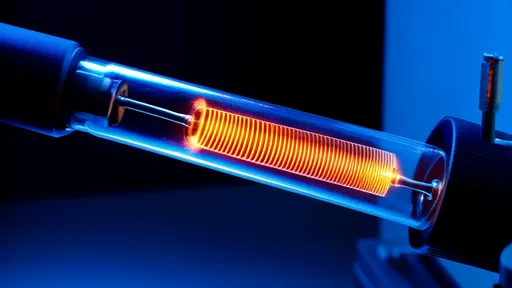

The principle is deceptively simple. When the mainspring of the clock delivers energy through the gear train, it imparts a impulse to the balance wheel, causing it to rotate. This rotation winds the hairspring, storing potential energy through elastic deformation. The spring then exerts a restoring torque, proportional to the angle of twist, pulling the balance wheel back toward its neutral position. This interplay of energy storage and release creates a continuous, oscillating motion. The frequency of this oscillation, measured in vibrations per hour, directly dictates the rate at which the clock ticks and, ultimately, its accuracy. The stiffer the spring, the greater the restoring force, and the faster the system will oscillate; a softer spring will result in a slower, more languid beat.

This behavior is beautifully described by Hooke's Law for torsion, which states that the restoring torque (τ) is proportional to the angular displacement (θ). The constant of proportionality is the spring's stiffness, often termed the torsional stiffness or the spring constant (k). The formula τ = -kθ reveals the fundamental linear relationship at the core of the system's operation. From this, we can derive the natural frequency of the oscillating system. The moment of inertia (I) of the balance wheel resists the acceleration caused by the spring's torque. Together, these two properties determine the period of oscillation (T) through the formula T = 2π√(I/k). The frequency (f), being the inverse of the period (f = 1/T), is therefore f = (1/2π)√(k/I). This equation is the master key. It tells us that the vibration frequency is directly proportional to the square root of the spring's stiffness and inversely proportional to the square root of the balance wheel's moment of inertia.

However, the real-world application is far more nuanced than this pristine formula suggests. The assumption of perfect linearity—that the spring constant k is truly constant—is an idealization. In reality, the material properties of the hairspring, its geometry, and even environmental factors introduce complexities. The quest for a material with perfect elasticity, minimal fatigue, and resistance to temperature changes has been a long one. Early iron and steel springs were susceptible to rust and magnetism and exhibited significant thermal expansion. A change in temperature would alter the Young's modulus of the spring material, effectively changing its stiffness (k) and thus throwing the clock's rate into error. This was a major obstacle in the pursuit of precision.

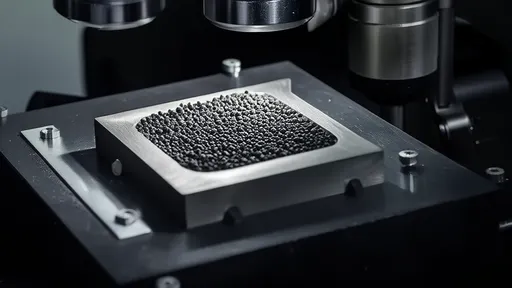

The development of specialized alloys like Elinvar (an alloy of nickel and steel) in the early 20th century marked a revolutionary leap forward. Elinvar, its name a contraction of "elasticité invariable" (invariable elasticity), has a modulus of elasticity that remains nearly constant over a wide range of temperatures. This single innovation dramatically reduced thermal error, making precision timekeeping accessible and reliable. Later, even more advanced materials like Nivarox and silicon were introduced. Silicon, manufactured using deep-reactive ion etching (DRIE) processes borrowed from the semiconductor industry, is not only immune to magnetism and corrosion but also exhibits remarkably consistent elastic properties, pushing the boundaries of accuracy even further.

Beyond material science, the geometry of the hairspring itself is a masterclass in mechanical engineering. The spring is not a simple flat spiral. Its cross-section, the pitch of the coils, and the shape of the curve all influence its behavior. A Breguet overcoil, perhaps the most famous geometric adjustment, is a testament to this. By lifting the outer coil of the spring and bending it into a distinct second curve, the legendary watchmaker Abraham-Louis Breguet achieved a more concentric expansion and contraction. This modification better centers the center of gravity of the spring system, mitigating positional errors that occurred when a clock was placed in different orientations (e.g., dial up vs. dial down). It effectively made the spring "breathe" more uniformly, enhancing isochronism.

Modern manufacturing techniques, including laser welding and photolithography, allow for an unprecedented level of control over these geometric parameters. Engineers can now design and produce springs with near-perfect terminal curves and optimized mass distribution, further refining the k in our fundamental equation. This precision engineering minimizes an array of subtle defects known to watchmakers as "middle error," "eccentricity error," and "pinning point error," all of which can cause the frequency to deviate from its theoretical value based on a simple linear model.

The relationship between deformation and frequency is also the basis of regulation. A clock is regulated by effectively altering the active length of the hairspring. This is done via a regulator index, a simple yet brilliant device that has two pins which can embrace a portion of the spring. Moving the regulator index shortens or lengthens the active portion of the spring that is free to flex. A shorter active length results in a effectively stiffer spring (a higher k), increasing the frequency and making the clock run faster. Conversely, a longer active length decreases stiffness, lowers the frequency, and slows the clock down. This provides the user with a straightforward means of fine-tuning the timekeeping rate, all by manipulating the very elastic property that drives the oscillation.

In conclusion, the dance between the elastic deformation of the hairspring and the vibration frequency of the balance wheel is a symphony of physics, materials science, and mechanical artistry. It is a relationship defined by a elegant mathematical law but perfected through centuries of empirical refinement and technological innovation. From the forging of temperature-resistant alloys to the microscopic etching of silicon components and the delicate bending of a Breguet overcoil, every advancement has been in service of honing this critical interaction. The steady tick-tock of a mechanical clock is therefore not just a sound of passing time; it is the audible manifestation of a perfect, ongoing struggle to harness and control the fundamental forces of elasticity and motion.

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025