The Maillard reaction, often colloquially referred to as browning, represents one of the most fundamental and complex series of chemical transformations in food science. While frequently mentioned in the same breath as caramelization, it is a distinctly separate process, primarily involving reactions between amino acids and reducing sugars. The threshold of this reaction, the precise point at which it begins to generate its characteristic flavor and color compounds, is not a single temperature but a dynamic curve, heavily influenced by a multitude of factors. Understanding this threshold curve, particularly in the context of temperature control, is paramount for chefs, food technologists, and manufacturers aiming to achieve consistent, high-quality results in products ranging from artisanal bread and roasted coffee to grilled steak and commercial gravy.

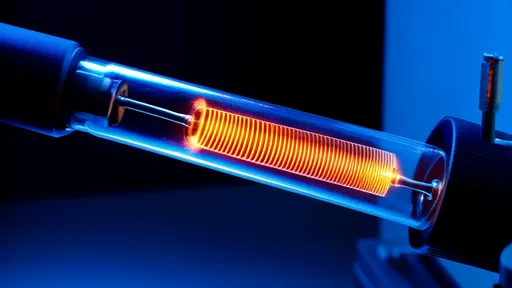

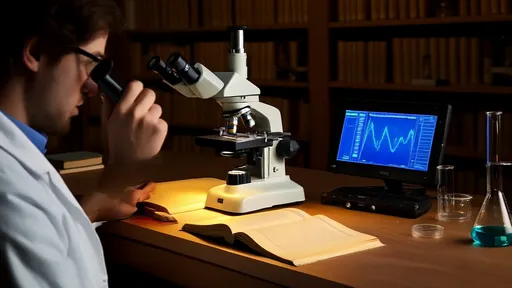

The foundational principle governing the Maillard threshold is that it is not a simple on/off switch activated at a specific degree. Early scientific work suggested a minimum initiation temperature around 140°C (284°F), but this is a drastic oversimplification. The reality is that the reaction rate is exponentially dependent on temperature. The relationship is often described by the Arrhenius equation, where for every 10°C increase in temperature, the rate of reaction approximately doubles. Therefore, what we perceive as a "threshold" is better visualized as a probability curve. At lower temperatures, say 110°C, the reaction may proceed, but at an imperceptibly slow rate. As heat is applied, the probability of the necessary molecular collisions occurring with sufficient energy increases dramatically, making the browning visible and organoleptically detectable within a practical timeframe.

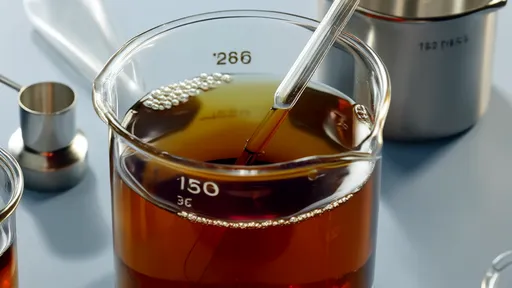

Water activity (aw) stands as a critical, and often overlooked, dictator of the Maillard threshold curve. The presence of water inhibits the reaction; it acts as a solvent and a diluent, reducing the concentration of reactants and lowering the temperature required for the reaction to proceed at a meaningful pace. This is why boiling, which occurs at 100°C, does not produce browning—the environment is too wet. As a food item heats and its surface dehydrates, the local water activity plummets. This is the pivotal moment. The surface transitions from a boiling or steaming state to a true dry-heat environment, allowing the local temperature to soar past the water's boiling point and rapidly cross the effective Maillard threshold. This explains why oven roasting is more effective at creating a crust than stewing, and why patting a steak dry before searing is a chef's classic trick for superior browning.

The pH of the cooking environment exerts a profound influence on the Maillard pathway. The reaction proceeds most efficiently in slightly alkaline conditions. This is a lever masterfully pulled in food preparation. A pinch of baking soda (a base) added to onions for caramelization or to the brine for pretzels (creating their characteristic dark brown "pretzel skin") actively lowers the effective Maillard threshold. The alkaline environment facilitates the formation of reactive intermediates, accelerating browning at a given temperature. Conversely, highly acidic environments, rich in ingredients like lemon juice or vinegar, suppress the reaction, raising the threshold and resulting in a paler product unless significantly more heat is applied.

The specific type of sugar and amino acid present creates a vast matrix of possible flavor outcomes, each with its own subtle kinetic nuances. For instance, the reaction between the amino acid cysteine and the sugar ribose is particularly potent and fast, generating meaty, savory sulfurous notes crucial for meat flavor. Fructose is more reactive than glucose. This compositional variable means that the "threshold curve" is not universal but is unique to the specific food matrix. A piece of fish, rich in certain amino acids, will have a different browning profile and flavor development curve than a piece of bread dough or a potato at the exact same oven temperature.

In industrial food production, controlling the Maillard reaction is not an art but a precise science of managing time-temperature profiles. Processes like spray drying, extrusion, and kettle cooking are meticulously designed to shepherd products through specific thermal pathways. The goal is often to maximize desirable flavor compounds like pyrazines (nutty, roasted notes) and furans (caramel, sweet notes) while minimizing the formation of off-flavors or potentially harmful compounds like acrylamide, which also forms under similar conditions. Advanced control systems manage the heating curve, holding temperatures at specific points for defined durations to hit the exact point on the threshold curve that yields the optimal flavor and color for that specific product.

For the culinary professional, this scientific understanding translates into powerful practical techniques. It moves beyond the simple instruction of "cook on high heat." It explains why a two-stage cooking process is often superior. An initial lower-temperature phase allows the interior of a food to come to the desired temperature without the surface overheating and burning. Then, a final blast of high heat rapidly dehydrates the surface and pushes it deep into the Maillard zone, creating a complex, flavorful crust. This is the principle behind reverse-searing a steak or finishing a roast in a very hot oven. It is the conscious manipulation of the temperature curve to navigate the Maillard threshold for a perfect result.

In conclusion, the Maillard reaction threshold is a sophisticated and dynamic interplay of thermal energy, time, and food chemistry. It is a curve, not a line—a landscape that can be navigated with skill. Mastery over this process, from the humble home kitchen to the high-tech food factory, hinges on the understanding that browning is not merely a function of heat, but a symphony conducted by the careful control of temperature over time, finely tuned by moisture, pH, and ingredient composition. This knowledge empowers the creation of depth, complexity, and that most sought-after quality in cooked foods: the perfect brown.

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025