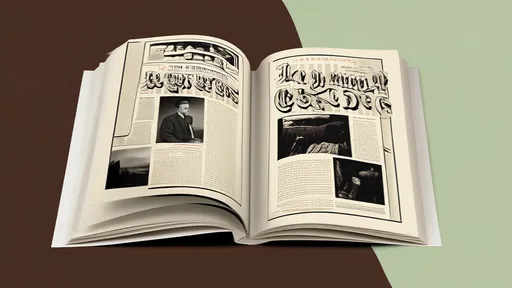

In the quiet halls of archaeological laboratories, a silent revolution is underway. Researchers are peering into the very molecular fabric of ancient texts, not with magnifying glasses, but with gas chromatographs. The study of cellulose degradation products through gas chromatography represents a frontier where chemistry meets history, offering unprecedented insights into the material lives of documents that have survived centuries, if not millennia.

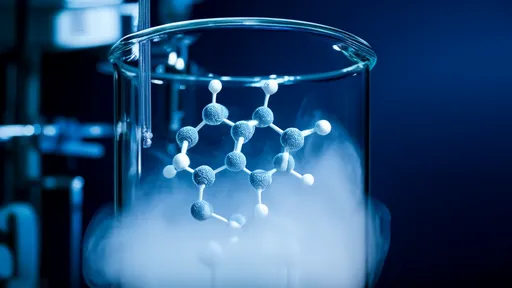

The premise is as elegant as it is complex. Cellulose, the primary structural component of plant cell walls and thus the paper, parchment, and papyrus that form our written heritage, undergoes predictable chemical transformations over time. As these materials age, environmental factors—humidity, temperature, microbial activity, and even the oils from human hands—initiate and accelerate degradation processes. The long polymer chains of cellulose break down, yielding a suite of smaller molecules: levoglucosan, furfural, hydroxy-methylfurfural, and various organic acids. It is this molecular fallout that scientists are now learning to read like a historical text.

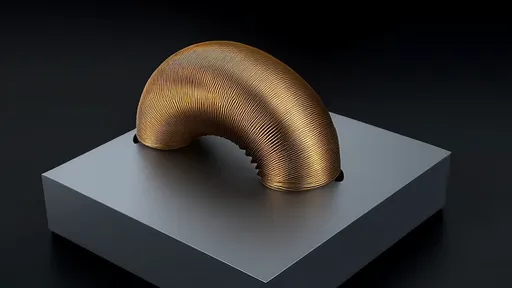

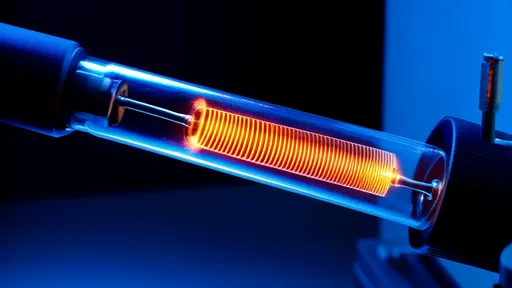

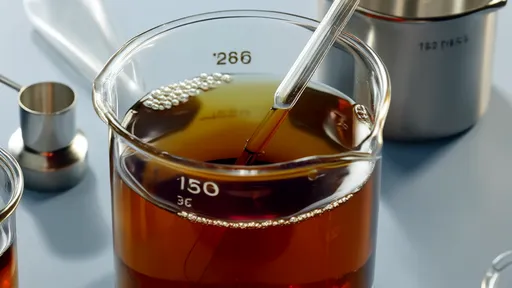

Gas chromatography (GC) has emerged as the premier tool for this molecular archaeology. The process is meticulous. A minuscule, often nearly invisible sample—a few fibers carefully excised from a margin or a damaged section of a ancient manuscript—understands solvent extraction. This liberates the diagnostic degradation compounds from the fibrous matrix. The resulting solution is then injected into the GC system. Inside the instrument's column, a delicate dance of chemistry and physics occurs: the mixture is vaporized and carried by an inert gas through a long, coiled column coated with a stationary phase.

As the vaporized compounds journey through this column, they separate based on their unique chemical affinities—their volatility and their interaction with the column's lining. Each compound exits the column at a distinct time, known as its retention time, creating a unique signature. A detector, typically a mass spectrometer coupled to the GC (GC-MS), then identifies and quantifies these eluting compounds. The result is a chromatogram: a complex peak-filled landscape that, to the trained eye, tells a detailed story of degradation.

The power of this technique lies in its specificity. Unlike broader methods of material analysis, GC-MS does not merely confirm the presence of degradation; it provides a quantitative and qualitative profile of it. The relative concentrations of levoglucosan to furans can indicate the dominant degradation pathways—whether hydrolytic, oxidative, or thermal. This is crucial. A manuscript degraded in the humid environment of a European monastery will have a different molecular fingerprint than a scroll preserved in the arid climate of an Egyptian tomb. This molecular data allows conservators to not only assess the current state of an artifact but also to diagnose its past environmental insults.

Furthermore, this molecular evidence is providing answers to long-standing questions in bibliographic studies. Forgeries, a perennial problem for historians and collectors, can sometimes be unmasked by their anachronistic degradation profiles. A document purported to be from the 15th century but showing a pattern of synthetic polymer degradation products from modern adhesives or a chemical signature indicative of artificial aging techniques would immediately raise red flags. Similarly, the technique can help authenticate discoveries. The much-debated Gospel of Jesus's Wife fragment, for instance, underwent rigorous material analysis, and while controversies remain, techniques like GC-MS contribute vital chemical data to the discussion about its provenance.

Perhaps the most profound application is in the field of preservation science. By understanding the precise chemical state of cellulose degradation, conservators can move beyond one-size-fits-all preservation strategies. The environmental controls for a collection can be fine-tuned based on the specific vulnerabilities revealed by the chromatographic analysis. If a set of documents shows advanced hydrolysis, controlling relative humidity becomes the paramount concern. If oxidative markers are dominant, then limiting exposure to light and pollutants is critical. This enables a new era of precision conservation, where limited resources can be directed toward the most effective interventions, thereby extending the lifespan of cultural treasures.

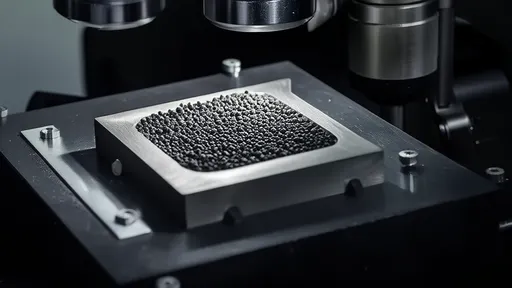

The challenges, however, are as significant as the promises. The field of ancient biomolecular analysis is fraught with the perils of contamination. Modern plastics, solvents, and even airborne pollutants can introduce foreign compounds that skew the chromatographic results. Consequently, the sample preparation must occur in ultra-clean environments, often in gloveboxes with filtered air. The act of sampling itself is a ethical minefield; the irreversible removal of material from an irreplaceable artifact is not undertaken lightly. This necessitates a close collaboration between chemists, conservators, and curators to ensure that the quest for knowledge does not come at the cost of physical damage.

Looking ahead, the future of molecular archaeology via gas chromatography is bright and expanding. Researchers are beginning to correlate specific degradation products with the activity of particular microbes or insect species, adding a biological dimension to the chemical narrative. There is also work on non-invasive or minimally invasive sampling techniques, such as using specialized tapes to capture surface compounds without removing any substrate material. As the databases of chromatographic profiles from known-period documents grow, so too will the power of this technique for comparative analysis and authentication.

In conclusion, the application of gas chromatography to the study of cellulose degradation in ancient texts is more than a technical achievement; it is a new form of dialogue with the past. We are no longer limited to reading the words inscribed on a page. We are now learning to read the page itself—its sufferings, its resilience, and its long journey through time. Each chromatogram is a biography written in molecules, revealing secrets about authenticity, origin, and age that were once thought to be forever lost to history. This silent conversation between modern science and ancient material ensures that these fragile links to our collective past are not only preserved but also better understood, allowing their stories to continue for generations to come.

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025