In the quiet hum of a textile research laboratory, something remarkable has been unfolding over the past decade—a discovery that challenges our fundamental understanding of natural fibers. Cotton, that most ancient and ubiquitous of materials, has been found to exhibit a peculiar and potentially transformative property when exposed to sunlight. It begins to absorb infrared radiation in ways that defy conventional textile science, a phenomenon now being termed "photon harvesting" in cotton fibers.

The story starts not with a eureka moment, but with a persistent anomaly in spectral data. Researchers measuring the thermal properties of sun-exposed fabrics noticed that cotton consistently showed unexpected infrared absorption peaks. At first dismissed as measurement error or contamination, these patterns persisted across samples from different sources, climates, and harvest years. The scientific community gradually awakened to the realization that ordinary cotton—the fabric of our everyday lives—was doing something extraordinary when interacting with sunlight.

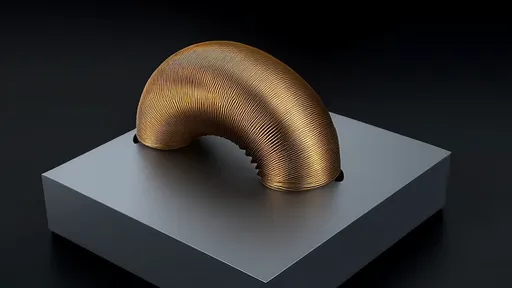

What makes this phenomenon particularly fascinating is its delayed nature. Unlike synthetic materials engineered for specific optical properties, cotton's infrared absorption doesn't occur immediately upon sunlight exposure. Instead, it develops gradually over hours of irradiation, suggesting some form of photochemical transformation within the cellulose structure. The fibers appear to be "learning" to absorb infrared, building this capacity through prolonged interaction with sunlight.

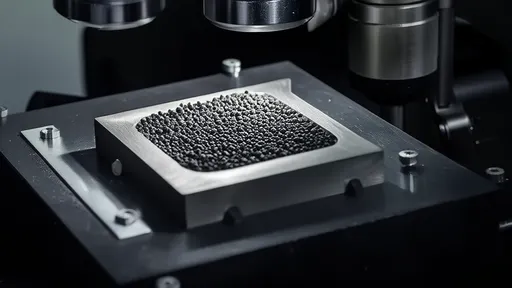

The mechanism behind this transformation appears rooted in cotton's complex biological origins. Unlike synthetic fibers with uniform molecular structures, cotton cellulose contains numerous "imperfections"—traces of pectins, waxes, and proteins that remain from the plant's growth process. These biological remnants, once considered impurities to be removed in processing, now appear crucial to the photon-harvesting phenomenon. They create what physicists call "defect states" within the material's electronic structure, providing pathways for infrared absorption that pure cellulose lacks.

Dr. Eleanor Shaw, whose team at the Natural Materials Institute has pioneered much of this research, explains it this way: "We're essentially seeing nature's version of doping in semiconductors. The biological 'impurities' in cotton create energy levels that allow the material to capture photons that would normally pass right through. It's a beautiful example of how nature's complexity creates functionality we're only beginning to understand."

The practical implications are staggering. Imagine clothing that naturally regulates body temperature by absorbing environmental infrared radiation. Or building insulation that adapts its thermal properties based on sun exposure. The energy savings potential alone has captured the attention of sustainability researchers worldwide. Unlike high-tech solutions requiring rare materials or complex manufacturing, this phenomenon works with ordinary, inexpensive cotton—one of the world's most produced natural fibers.

What's particularly remarkable is how this property varies with cotton's origin. Research comparing cottons from different growing regions shows distinct infrared absorption signatures. Egyptian cotton develops different patterns than Texas upland cotton, suggesting that soil composition, climate, and even farming practices might influence the photon-harvesting capabilities. This has sparked interest among agricultural researchers studying how growing conditions might be optimized not just for fiber quality, but for optical properties.

The time-dependent nature of the effect presents both challenges and opportunities. Unlike permanent material treatments, cotton's infrared absorption capacity fades when the material is kept in darkness, then rebuilds upon re-exposure to sunlight. This reversible quality suggests applications in smart textiles that respond to environmental conditions. A cotton garment might provide extra warmth after a morning in the sun, then gradually return to normal as the day progresses.

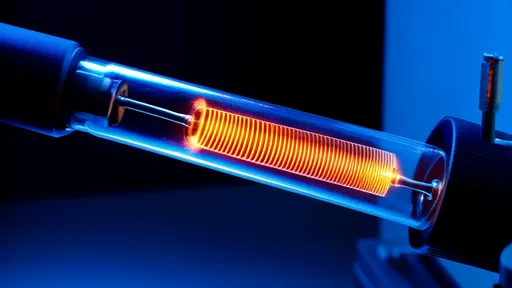

Recent studies have begun mapping the specific wavelengths involved. The absorption isn't uniform across the infrared spectrum but shows particular strength in certain bands corresponding to atmospheric transmission windows. This suggests an almost eerie adaptation to Earth's specific environmental conditions—as if cotton has evolved to interact optimally with our planet's sunlight filtered through its atmosphere.

Manufacturers are taking notice. Several major textile companies have established research partnerships to explore how this natural phenomenon might be enhanced or controlled. The challenge lies in balancing the infrared absorption with other fabric properties—no one wants clothing that becomes uncomfortably warm in sunlight. Early approaches focus on blend fabrics that combine cotton with other fibers to moderate the effect while still benefiting from the photon harvesting.

The discovery also raises fascinating questions about cotton's natural history. Why would a plant fiber evolve such properties? Some researchers speculate it might relate to seed protection—infrared absorption could help regulate temperature in the cotton boll. Others suggest it might be incidental, a byproduct of other adaptations. Whatever its evolutionary origin, humanity now stands to benefit from this hidden property of a material we've used for millennia.

As research continues, scientists are developing more precise models of the phenomenon. Advanced spectroscopy techniques are mapping the molecular changes during sunlight exposure, while quantum chemistry simulations are helping understand the precise mechanisms at the atomic level. Each discovery reveals additional layers of complexity, suggesting that cotton's interaction with light is far more sophisticated than anyone imagined.

This isn't just laboratory curiosity. Field tests are already underway with architectural fabrics, agricultural textiles, and of course, clothing. Early results show promise for reducing energy consumption in buildings using cotton-based insulation that actively manages heat transfer based on sun exposure. The potential for reducing air conditioning loads in hot climates particularly excites sustainability experts.

The phenomenon also appears in historical context. Textile conservators have noted that sun-exposed antique cotton textiles often show different aging patterns than those stored in darkness. What was once considered simple photodegradation now appears to involve more complex photochemical processes. This new understanding may lead to better preservation techniques for museum collections.

Looking forward, researchers are exploring whether similar effects occur in other natural fibers. Preliminary studies show linen exhibiting related phenomena, though with different spectral signatures. Wool and silk show minimal effects, suggesting the phenomenon relates specifically to plant cellulose and its biological companions. This focus on natural materials represents a broader shift in materials science toward understanding and leveraging biological complexity rather than trying to eliminate it.

For consumers, the practical applications may soon become visible. Several outdoor apparel companies are developing cotton-blend fabrics that use this phenomenon for temperature regulation. Unlike high-tech phase-change materials or electrical heating elements, these fabrics work passively, requiring no energy input beyond sunlight. The marketing potential is obvious, but researchers caution that real-world performance depends on many factors including weave density, dyeing, and finishing processes.

The scientific community remains appropriately cautious but genuinely excited. As one researcher noted, "We've been wearing cotton for five thousand years and we're still discovering new things about it. It reminds us that nature often holds solutions right in front of us, waiting for us to develop the tools to see them." This humility before nature's complexity characterizes much of the current research.

What began as an anomalous measurement has grown into a multidisciplinary research field spanning materials science, photonics, botany, and textile engineering. The story of cotton's hidden light-manipulating abilities continues to unfold, reminding us that even the most familiar materials can surprise us when examined with fresh eyes and new technologies. As research progresses, we may find that nature has been providing advanced materials all along—we just needed to learn how to see their full capabilities.

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025